What makes Ireland so interesting is two things that both affected the nature of inmigration over thousands of years.

The first and most important is that all inmigration was generally modest. Of course forced out migration initially peopled the USA with whites far more than either the English or the Scots.

The second factor long forgotten is that Ireland or more exactly, the isle of Lewis was the northern terminus of the Atlantic Great Circle route which included Spain., Portugal the Canary islands and the whole Atlantic Seaboard of the USA with the Bahamas. This route was reactivated by the Templars prior to Columbus and this explains the real importance of Scotland to the Templars.

I also presume that the route truly was never fully abandoned either after it served from 2500 BC through 1159 BC as the central conduit of the copper trade of the Atlantean global sea trade empire. The Templars simply inherited what had already existed.

What this meant for Ireland is that a steady stream of shipping passed trough the Irish Sea and surely used the eastern coast as a landing and refit base. Thus we have a steady stream of black Irish trickling in.

It is noteworthy that the husbandry of red deer as riding mounts occurs here and in Georgia. This all ended in Ireland with the advent of riding horses in the early Iron Age. .

However before all that the earliest settlers were the same folk who settled the Mediterranean around 6500 years ago with their agricultural tool kit. That initial wave came easily by sea. Then we had a later land based expansion out of those steppes into the forests of Europe that also finally reached Ireland and clearly tackled the more difficult task of clearing forests. Thus the two earliest waves that provided the background genetics.

.

Blood of the Irish: What DNA Tells Us About the Ancestry of People in Ireland

The red-hair gene is most common in among Scottish and Irish people.

Source Blood of the Irish

The

blood in Irish veins is Celtic, right? Well, not exactly. Although the

history that used to be taught at school said the Irish were simply a

Celtic people, related to the central European Celts, the truth is much

more complicated, and much more interesting than that.

Research done into the DNA of the Irish has shown that our old understanding of where the population of Ireland originated may have been misguided. Although the modern Irish have been shown to share many genetic similarities with Scottish and Welsh populations, and to differ somewhat from the English, due to repeated waves of migration to the island they also have close genetic relations with people further afield. In fact, some of the Irish's closest DNA links are with regions further afield!

This article is based upon the latest research sequencing the genomes of the remains of ancient Irish people, published at the end of 2015

.

Research done into the DNA of the Irish has shown that our old understanding of where the population of Ireland originated may have been misguided. Although the modern Irish have been shown to share many genetic similarities with Scottish and Welsh populations, and to differ somewhat from the English, due to repeated waves of migration to the island they also have close genetic relations with people further afield. In fact, some of the Irish's closest DNA links are with regions further afield!

This article is based upon the latest research sequencing the genomes of the remains of ancient Irish people, published at the end of 2015

.

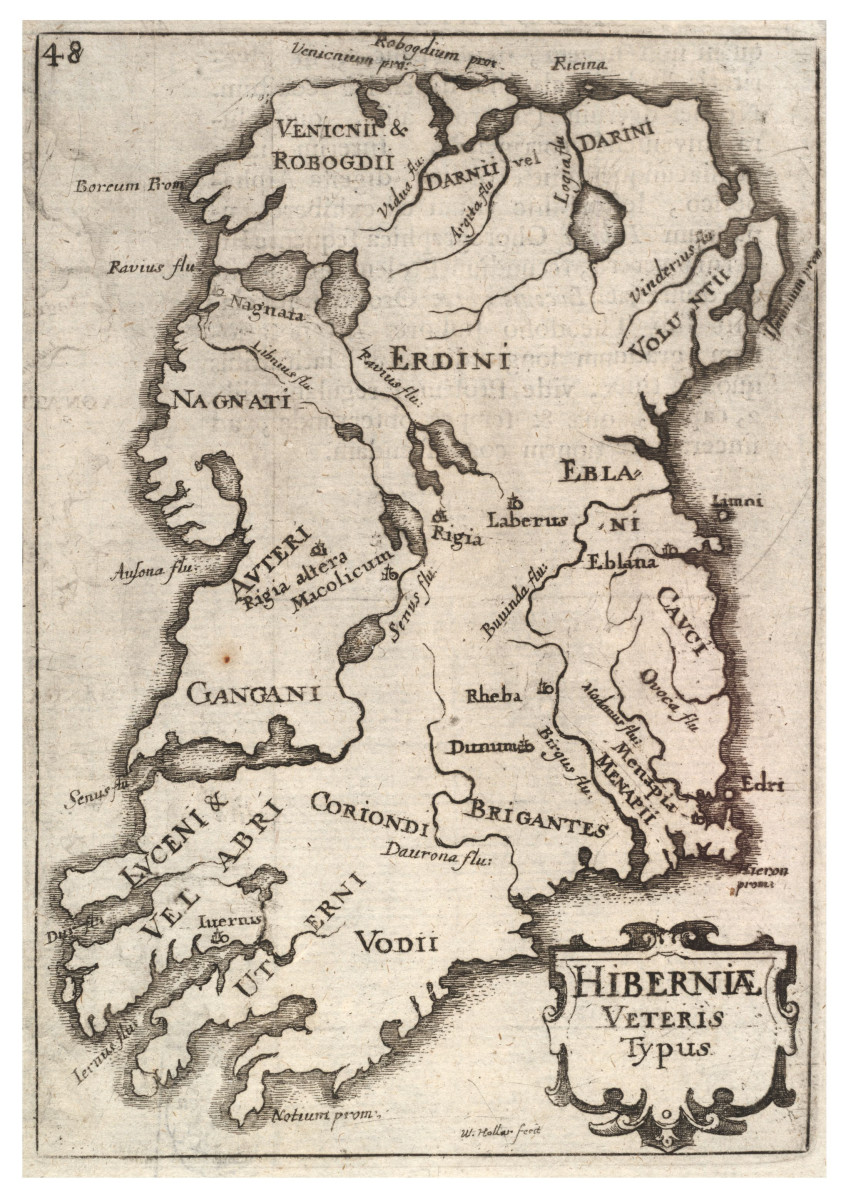

Medieval map of Ireland, showing Irish tribes.

Early Origins of Irish DNA

The

earliest settlers came to Ireland during the Stone Age, around 10,000

years ago. There are still remnants of their presence scattered across

the island. Mountsandel in Coleraine in the North of Ireland is the

oldest known site of settlement in Ireland—remains of woven huts, stone

tools and food such as berries and hazelnuts were discovered at the site

in 1972.

Where Did the Early Irish Come From?

For a long time the myth of Irish history has been that the Irish are Celts. Many people still refer to Irish, Scottish, and Welsh as Celtic culture. The assumption has been that they were Celts who migrated from central Europe around 500BCE.

Keltoi was the name given by the Ancient Greeks to a 'barbaric' (in their eyes) people who lived to the north of them in central Europe. While early Irish art shows some similarities of style to central European art of the Keltoi, historians have also recognized many significant differences between the two cultures.

Recent research into Irish DNA at the beginning of the twenty-first century suggests that the early inhabitants of Ireland were not directly descended from the Keltoi of central Europe. Genome sequencing performed on remains of early settlers in Ireland by researchers at Trinity University in Dublin and Queens University has revealed at least two waves of migration to the island in past millennia. Analysis of the remains of a 5,200 year-old Irish farmer suggested that the population of Ireland at that time was closely genetically related to the modern-day populations of southern Europe, especially Spain and Sardinia. Her ancestors, however, originally migrated from the Middle East, the cradle of agriculture.

Meanwhile, the research team also examined the remains of three 4,000 year-old men from the Bronze Age and revealed that another wave of migration to Ireland had taken place, this time from the edges of Eastern Europe. One third of their ancestry came from the Steppe region of Russia and Ukraine, so their ancestors must have gradually spread west across Europe. These remains, found on Rathlin Island also shared a close genetic affinity with the Scottish, Welsh, and modern Irish, unlike the earlier farmer. This suggests that many people living in Ireland today have genetic links to people who were living on the island at least 4,000 years ago.

Where Did the Early Irish Come From?

For a long time the myth of Irish history has been that the Irish are Celts. Many people still refer to Irish, Scottish, and Welsh as Celtic culture. The assumption has been that they were Celts who migrated from central Europe around 500BCE.

Keltoi was the name given by the Ancient Greeks to a 'barbaric' (in their eyes) people who lived to the north of them in central Europe. While early Irish art shows some similarities of style to central European art of the Keltoi, historians have also recognized many significant differences between the two cultures.

Recent research into Irish DNA at the beginning of the twenty-first century suggests that the early inhabitants of Ireland were not directly descended from the Keltoi of central Europe. Genome sequencing performed on remains of early settlers in Ireland by researchers at Trinity University in Dublin and Queens University has revealed at least two waves of migration to the island in past millennia. Analysis of the remains of a 5,200 year-old Irish farmer suggested that the population of Ireland at that time was closely genetically related to the modern-day populations of southern Europe, especially Spain and Sardinia. Her ancestors, however, originally migrated from the Middle East, the cradle of agriculture.

Meanwhile, the research team also examined the remains of three 4,000 year-old men from the Bronze Age and revealed that another wave of migration to Ireland had taken place, this time from the edges of Eastern Europe. One third of their ancestry came from the Steppe region of Russia and Ukraine, so their ancestors must have gradually spread west across Europe. These remains, found on Rathlin Island also shared a close genetic affinity with the Scottish, Welsh, and modern Irish, unlike the earlier farmer. This suggests that many people living in Ireland today have genetic links to people who were living on the island at least 4,000 years ago.

Irish Origin Myths Confirmed by Scientific Evidence?

One of the oldest texts composed in Ireland is the Leabhar Gabhla,

the Book of Invasions. It tells a semi-mythical history of the waves of

people who settled in Ireland in earliest times. It says the first

settlers to arrive in Ireland were a small dark people called the Fir

Bolg, followed by a magical super-race called the Tuatha de Danaan (the

people of the goddess Dana).

Most interestingly, the book says that the group which then came to Ireland and fully established itself as rulers of the island were the Milesians—the sons of Mil, a soldier from Spain. Modern DNA research has actually suggested that the Irish are close genetic relatives of the people of northern Spain.

What we do know is that the modern Irish are descended from a number of waves of migration with some ancestors coming from as far away as the Middle East and the Russian Steppes. Although it might seem surprising, it is worth remembering that in ancient times the sea was one of the fastest and easiest ways to travel. When the land was covered in thick forest, coastal settlements were common and people travelleled around the seaboard of Europe quite freely.

Most interestingly, the book says that the group which then came to Ireland and fully established itself as rulers of the island were the Milesians—the sons of Mil, a soldier from Spain. Modern DNA research has actually suggested that the Irish are close genetic relatives of the people of northern Spain.

What we do know is that the modern Irish are descended from a number of waves of migration with some ancestors coming from as far away as the Middle East and the Russian Steppes. Although it might seem surprising, it is worth remembering that in ancient times the sea was one of the fastest and easiest ways to travel. When the land was covered in thick forest, coastal settlements were common and people travelleled around the seaboard of Europe quite freely.

Are the Basques the Closest Genetic Relatives of the Irish?

Today,

people living the north of Spain in the region known as the Basque

Country share many DNA traits with the Irish. However, the Irish also

share their DNA to a large extent with the people of Britain, especially

the Scottish and Welsh.

DNA testing through the male Y chromosome has shown that Irish males have the highest incidence of the haplogroup 1 (or Rb1) gene in Europe. While other parts of Europe have integrated continuous waves of new settlers from Asia, Ireland's remote geographical position has meant that the Irish gene-pool has been less susceptible to change. The same genes have been passed down from parents to children for thousands of years. The other region with very high levels of this male chromosome is the Basque region.

This is mirrored in genetic studies which have compared DNA analysis with Irish surnames. Many surnames in Irish are Gaelic surnames, suggesting that the holder of the surname is a descendant of people who lived in Ireland long before the English conquests of the Middle Ages. Men with Gaelic surnames, showed the highest incidences of Haplogroup 1 (or Rb1) gene. This means that those Irish whose ancestors pre-date English conquest of the island are descendants (in the male line) of people who probably migrated west across Europe, as far as Ireland in the north and Spain in the south.

Some scholars even argue that the Iberian peninsula (modern-day Spain and Portugal) was once heavily populated by Celtiberians who spoke at now-extinct Celtic language. They believe some of these people moved northwards along the Atlantic coast bringing Celtic language and culture to Ireland and Britain, as well as France. Although the evidence in not conclusive, the findings on the similarities between Irish and Iberian DNA provides some support for this theory.

DNA testing through the male Y chromosome has shown that Irish males have the highest incidence of the haplogroup 1 (or Rb1) gene in Europe. While other parts of Europe have integrated continuous waves of new settlers from Asia, Ireland's remote geographical position has meant that the Irish gene-pool has been less susceptible to change. The same genes have been passed down from parents to children for thousands of years. The other region with very high levels of this male chromosome is the Basque region.

This is mirrored in genetic studies which have compared DNA analysis with Irish surnames. Many surnames in Irish are Gaelic surnames, suggesting that the holder of the surname is a descendant of people who lived in Ireland long before the English conquests of the Middle Ages. Men with Gaelic surnames, showed the highest incidences of Haplogroup 1 (or Rb1) gene. This means that those Irish whose ancestors pre-date English conquest of the island are descendants (in the male line) of people who probably migrated west across Europe, as far as Ireland in the north and Spain in the south.

Some scholars even argue that the Iberian peninsula (modern-day Spain and Portugal) was once heavily populated by Celtiberians who spoke at now-extinct Celtic language. They believe some of these people moved northwards along the Atlantic coast bringing Celtic language and culture to Ireland and Britain, as well as France. Although the evidence in not conclusive, the findings on the similarities between Irish and Iberian DNA provides some support for this theory.

The Kingdom of Dalriada c 500 AD is marked in green. Pictish areas marked yellow.

Irish and British DNA: A Comparison

I

live in Northern Ireland and in this small country the differences

between the Irish and the British can still seem very important. Blood

has been spilt over the question of national identity.

However, research into both British and Irish DNA suggests that people on the two islands have much genetically in common. Males in both islands have a strong predominance of the Haplogroup 1 gene, meaning that most of us in the British Isles are descended from the same stone age settlers.

The main difference is the degree to which later migrations of people to the islands affected the population's DNA. Parts of Ireland (most notably the western seaboard) have been almost untouched by outside genetic influence since early times. Men there with traditional Irish surnames have the highest incidence of the Haplogroup 1 gene - over 99%.

At the same time London, for example, has been a mutli-ethnic city for hundreds of years. Furthermore, England has seen more arrivals of new people from Europe - Anglo-Saxons and Normans - than Ireland. Therefore while the earliest English ancestors were very similar in DNA and culture to the tribes of Ireland, later arrivals to England have created more diversity between the two groups.

Irish and Scottish people share very similar DNA. The obvious similarities of culture, pale skin, tendency to red hair have historically been prescribed to the two people's sharing a common Celtic ancestry. Actually, in my opinion, it seems much more likely that the similarity results from the movement of people from the north of Ireland into Scotland in the centuries 400 - 800 AD. At this time the kingdom of Dalriada, based near Ballymoney in County Antrim extended far into Scotland. The Irish invaders brought Gaelic language and culture, and they also brought their genes.

However, research into both British and Irish DNA suggests that people on the two islands have much genetically in common. Males in both islands have a strong predominance of the Haplogroup 1 gene, meaning that most of us in the British Isles are descended from the same stone age settlers.

The main difference is the degree to which later migrations of people to the islands affected the population's DNA. Parts of Ireland (most notably the western seaboard) have been almost untouched by outside genetic influence since early times. Men there with traditional Irish surnames have the highest incidence of the Haplogroup 1 gene - over 99%.

At the same time London, for example, has been a mutli-ethnic city for hundreds of years. Furthermore, England has seen more arrivals of new people from Europe - Anglo-Saxons and Normans - than Ireland. Therefore while the earliest English ancestors were very similar in DNA and culture to the tribes of Ireland, later arrivals to England have created more diversity between the two groups.

Irish and Scottish people share very similar DNA. The obvious similarities of culture, pale skin, tendency to red hair have historically been prescribed to the two people's sharing a common Celtic ancestry. Actually, in my opinion, it seems much more likely that the similarity results from the movement of people from the north of Ireland into Scotland in the centuries 400 - 800 AD. At this time the kingdom of Dalriada, based near Ballymoney in County Antrim extended far into Scotland. The Irish invaders brought Gaelic language and culture, and they also brought their genes.

Irish Characteristics and DNA

The

MC1R gene has been identified by researchers as the gene responsible

for red hair as well as the accompanying fair skin and tendency towards

freckles. According to genetic research, genes for red hair first

appeared in human beings about 40,000 to 50,000 years ago.

These genes were then brought to the British Isles by the original settlers, men and women who would have been relatively tall, with little body fat, athletic, fair-skinned and who would have had red hair. So red-heads may well be descended from the earliest ancestors of the Irish and British.

These genes were then brought to the British Isles by the original settlers, men and women who would have been relatively tall, with little body fat, athletic, fair-skinned and who would have had red hair. So red-heads may well be descended from the earliest ancestors of the Irish and British.

Who Are the "Black Irish"?

The

origin of the term "Black Irish" and the people it describes are

debated (see the comments below!). The phrase is ambiguous and is mainly

used outside of Ireland to describe dark-haired people of Irish origin.

The ambiguity comes in when trying to determine whether dark-haired Irish people are genetically distinct from Irish with lighter coloring. Dark hair is common in Ireland, while dark complexions are more rare.

One theory about the origins of the term is that it describes Irish people who descend from survivors of the Spanish Armada. There are other hypotheses, mostly placing Irish ancestors on the Iberian peninsula or among the traders that sailed back and forth between Spain, North Africa, and Ireland, particularly around the Connemara region.

Some "Black Irish" are of Irish-African descent, tracing their ancestry back to the slave trade. Many of these people live on Barbados and Montserrat.

Some readers, writing below, with typical Black Irish coloring have had genetic testing done to confirm that they have Spanish, Portuguese, and Canary Island heritage.

The ambiguity comes in when trying to determine whether dark-haired Irish people are genetically distinct from Irish with lighter coloring. Dark hair is common in Ireland, while dark complexions are more rare.

One theory about the origins of the term is that it describes Irish people who descend from survivors of the Spanish Armada. There are other hypotheses, mostly placing Irish ancestors on the Iberian peninsula or among the traders that sailed back and forth between Spain, North Africa, and Ireland, particularly around the Connemara region.

Some "Black Irish" are of Irish-African descent, tracing their ancestry back to the slave trade. Many of these people live on Barbados and Montserrat.

Some readers, writing below, with typical Black Irish coloring have had genetic testing done to confirm that they have Spanish, Portuguese, and Canary Island heritage.

No comments:

Post a Comment